The Grand Rue

Roads as Thoroughfares of Life

Myron Beasley and Robert August Peterson

The Grand Rue is a city symphony of sounds featuring audio collected three days before the devastating 2010 earthquake in Port-Au-Prince, Haiti.

About Grand Rue

Their story begins on ground level, with footsteps. They are myriad, but do not compose a series. They cannot be counted because each unit has a qualitative character: a style of tactile apprehension and kinesthetic appropriation. Their swarming mass is an innumerable collection of singularities. Their intertwined paths give their shape to spaces. They weave places together. In that respect, pedestrian movements form one of these "real systems whose existence in fact makes up the city." They are not localized; it is rather they that spatialize. - Michel De Certeau

The Grand Rue is a road that goes through the center of Port-Au-Prince. On the official map of the city the name Grand Rue does not appear, rather inscribed in its place is Blvd. Jn. Jacques Dessalines, the name of the great leader of the slave rebellion and later self-proclaimed emperor of Haiti. But to all who reside on the island, this road, this major thoroughfare and the community of which it surrounds is referred to simply as the Grand Rue. Perhaps it is called Grand Rue because of its expansive length as it protrudes through the busy conurbation linking various neighborhoods with commerce. The true width of the street is disguised for the spillage of people and cars pushing their way through the bustling boulevard. The narrow sidewalks are claimed by street vendors selling everything from lumber and automobile fragments, to fresh fruits and freshly fried goat from cooks hovering over piping hot cauldron of oil. The “Grand Rue” is a city symphony, a composition of sounds from a complete day on this major thoroughfare that demonstrates that roads can “become liberated spaces that can be occupied,” as de Certeau puts it.

Myron and Rob’s Background in Haiti

In February 2014, Provoke! co-editor Mary Caton Lingold interviewed Myron and Robert about their project. In the following audio recordings, the co-creators of “Grand Rue.” delve into the inspiration behind the piece and their process creating it.

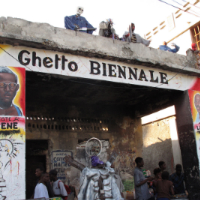

Myron and Robert connected in Haiti at the first Ghetto Biennale, a gathering of scholars and artists in the Grand Rue neighborhood of Port-Au-Prince in 2009. It was during this gathering that Robert made the audio recordings that serve as the raw material for “Grand Rue.” In this excerpt, Rob discusses how frustration with the North American bias and Eurocentricity of his formal arts education in an MFA program led him to Haiti to learn from the artists of the Grand Rue.

Myron began working in Haiti as an ethnographer, eager to follow in the footsteps of Zora Neale Hurston, who did extensive anthropological work in the region. Myron has spent a lot of time in Jacmel and written about underground food economies and women who work in the streets. He also studies the Grand Rue Artist and works as a curator of the Ghetto Biennale series.

The Earthquake's Impact

The recordings used in Grand Rue were made mere days before the devastating 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Here, Myron and Rob respond to Mary Caton's question, “How did the earthquake impact the direction of the project, your collaboration, and the significance of the recordings that you had made?” In their response, the collaborators explain the impact technology had on the flow of communication in the wake of the earthquake. They also explore the way their personal grief at first presented difficulty, but later became the grounds for executing their vision for this project.

Ideas Behind the Project

The project co-creators discuss the concepts behind the piece and how they approached capturing the flow of life in the street in Port-Au-Prince. As Myron says, "there is a flow of life, a stream that is absolutely beautiful ... to walk through a street can in many ways tell us a huge story about life.” Rob adds that "life happens in the road because that’s where the respite actually is…. in Haiti, and in and along the most of the places that approaches the equator, they take respite in the road because that’s where the breeze is and where the cold beverages are, and during the night where the fires and the televisions are."

Myron and Rob explain their understanding of “soundscape,” the importance of silence to the creation of the piece, and the unanticipated connections between the postmodern avant guard (such as John Cage) and the Grand Rue artists.

Technical Design: The Vision and the Equipment

Here the collaborators offer their technical vision for creating the project, which was to “take the hand of the media out of the piece” by creating an immersive, multi-channel listening experience. Rob explains why sound was the appropriate medium for this piece.

Rob names the equipment he used to record and edit the project, explaining his belief in the importance of using open-source software and commercially available resources. He feels that the stigma of media art as expensive and necessitating expertise prevents a lot of people from attempting this kind of work. His message: go for it!

On Collaboration and Storytelling

About the Contributors

Myron M. Beasley, PhD is Associate Professor of American Cultural Studies and African American Studies at Bates College.

Robert Peterson, MFA, is a sound artist and curator from Louisiana. He is currently based in New York City.